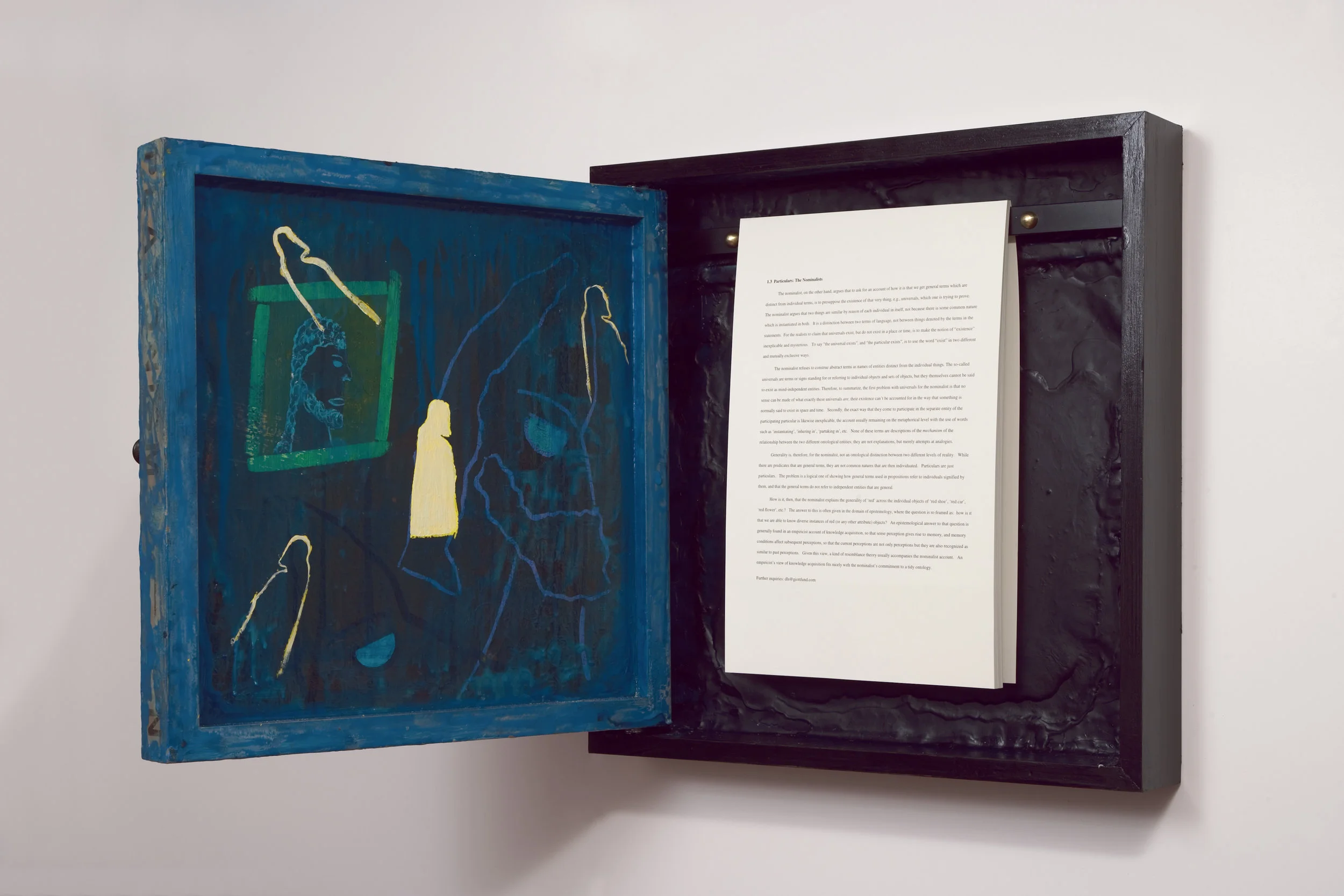

The Platonist

2007

oil on canvas in wooden box with tear-off text

18″ x 12″ x 2″

1.1 Generality

Generality is arguably an essential feature of our experience of particular objects. The fact that a general, apparently stable term such as ‘red’ exhibits itself as varyingly as a red shoe, a red car, a red flower, a red suit, etc., gives rise to the question regarding the ontological character of the general term “red” and in what way it is different from the objects to which it is applied. Since this generality is reflected in both thought and language, we must ask how the mental concepts reflecting this generality are formed, and how is it that we come by these general concepts when the experiences from which they are formed are only particular.

Let us take as an aesthetic example, the concept “The Beautiful”. We experience diverse particular things as beautiful, e.g., “the boy is beautiful”, or “the flower is beautiful”, or “the car is beautiful”. In ways the realist must make clear, the attribute or quality called “beauty” has successfully been attributed to these different objects, in seemingly the same way that the color red had been attributed to them in the prior example. The general attribute “beautiful”, like the general attribute “red”, is commonly contrasted with the numerically unique and spatially discreet particulars or objects to which it is said to apply.

1.2Universals: The Realists/Platonists

Those who find this linguistic distinction between the general and the particular reflective of the ontological facts of the world identify these generalities as universals, and give them the status of mind-independent entities, so that, even if there were no cognizing minds to perceive the general in the particular, the realist would say these universals would still exist. Thus the common attribute “man” is a single reality that is instantiated in both Socrates and in my father, and in all other men. It is the universal in all the particulars.

And while that entity called “man” is included in every particular judgment where upon we have seen a particular male, it is not from ordinary sense experience by which we learn of its existence. For the realist who argues for universals, we are aware of universals not by sense itself but by reason - through the process of recognizing that the same ‘red’ which is being applied to the object “car”, is identical with the “red” which is being applied to the object “flower”.

The universals are a type of entity, e.g., “the one”, which can simultaneously manifest itself in different instances of the other class of entity, e.g., the particulars – “the many”. Given that there are two very different kinds of entities, then, which make up the composition of the world - on this view - it is the realist, having structured this view, who takes the existence of universals to be true, for if all the individual objects called by the same name, for example, ‘red’, had nothing in common but being called ‘red’, no reason could be given why just they and no other objects had that name. In other words, in the absence of universals as an explanation, no reason could be given for deciding whether or not to include an object in the category of things for which the attribute red applies.