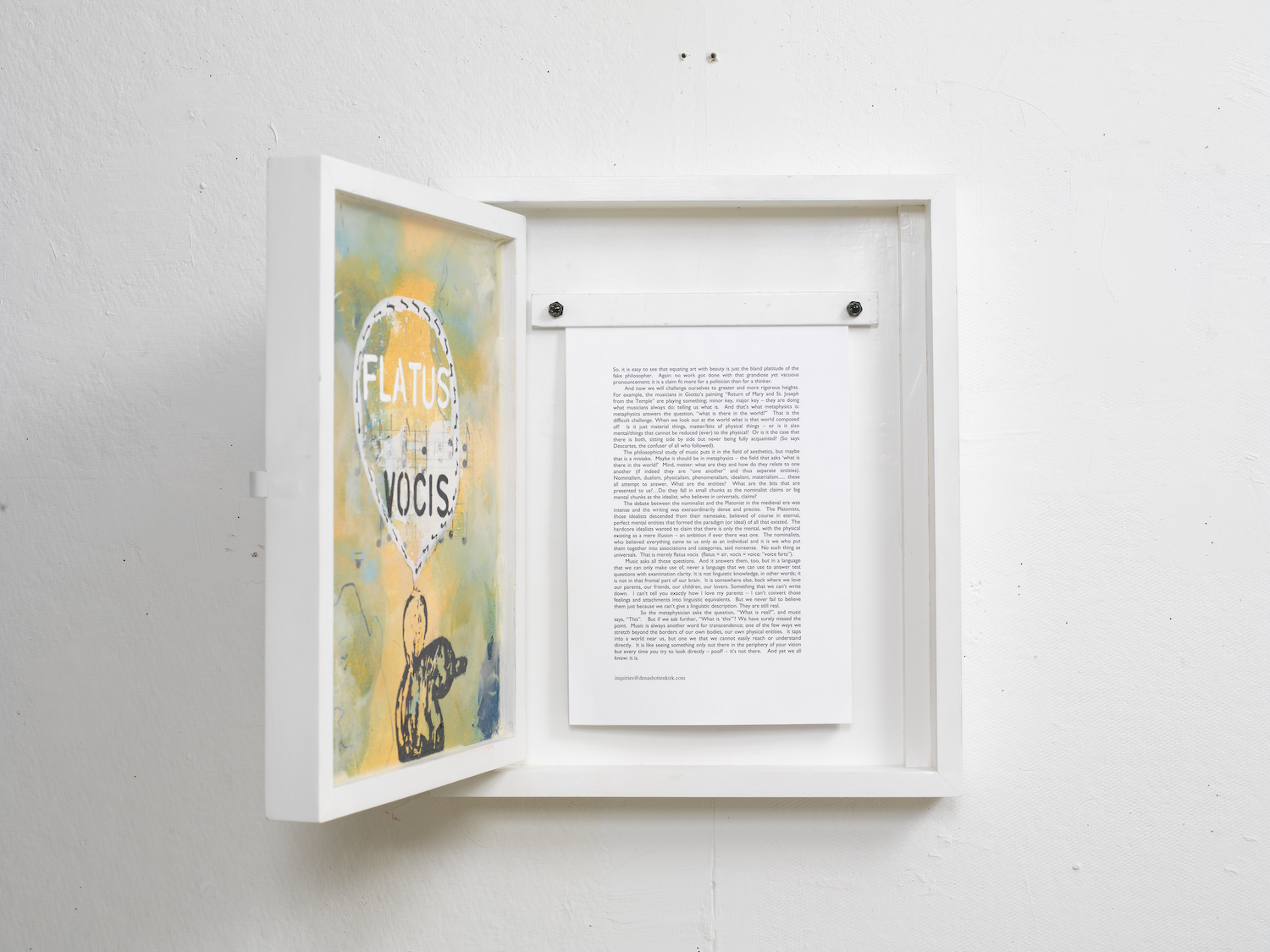

Flatus Vocis I

2007

oil on canvas in wooden box with tear-off text

18″ x 12″ x 2″

So, it is easy to see that equating art with beauty is just the bland platitude of the fake philosopher. No work got done with that grandiose yet vacuous pronouncement; it is a claim fit more for a politician than for a thinker.

And we should challenge ourselves to greater and more rigorous heights. For example, we should face the following difficult fact. How art comes to translate meaning from the inert object to the viewer is much more complex and interesting than simply tagging the banner “beautiful” on to it. Take music for example.

No one can really (yet) explain how music affects us the way it does or even what it means to say that it affects us. We know it uses a language in the form of notes, rhythm, patterns, etc. There is a craft to it and that can be conveyed, but that tells us very little for no one can tell us exactly what happens to us when we listen to a piece of music. What makes it go from just noise in our brains to music? (And there are those rare people with a certain kind of neurological damage to the brain that allows them to hear only the sounds and never the music; they remain mystified that people are responding to the clanging and clatter.)

Nor can anyone really explain exactly the language that music uses. How exactly does a piece of music convey, for example, sadness? Some know-it-alls would ‘explain’ that that happens when the piece is in a minor key or when a mournful chord is struck. But that’s not an explanation, that’s just of description; that’s saying nothing more than saying it’s sad. They’ve just substituted the word “minor key” for the word “sad”.

The question is how is it sad to us? What language is that – that minor key – that means sadness to us? How does a minor key match those chemicals that surge through our brain when we are sad because a loved one died or left us? Or more pertinently, how does the minor cause those chemicals to surge through our brain – the same chemicals that surged through our brain when our loved one died or left us?

That’s the question that deserves a causal explanation, but we don’t have one. Why do humans feel a particular way when they hear minor keys? Or why another thing when sharply dissonant notes are played? Why is it that the “sad” music makes us re-connect to other brain states that we call “sad”? Why does a sad piece of music get called “sad” just like the death of a loved one is called “sad”? What do these two things – sad music and a sad event – have in common? Why are our brain states in those moments so similar? What is the minor key doing to us?

The musicians in Giotto’s painting “Return of Mary and St. Joseph from the Temple” are playing something, but we don’t know what. Minor key, major key; they are doing what musician always do: telling us what is. And that’s what metaphysics is: metaphysics answers the question, “what is there in the world?” When we look out at the world what is that world composed of? Is it just material things - matter – bits of physical things, or is it also mental – things that cannot be reduced (ever) to the physical? Or is it the case that there is both, sitting side by side but never being fully acquainted? (Descartes, the confuser of all who followed). Or, as the idealists claim, is there only the mental, with the physical existing only as a mere illusion – an ambition if ever there was one.